Bloomberg News

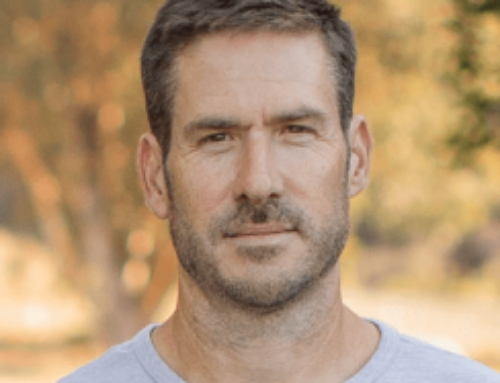

(Bloomberg) — Stanley Fischer, a professor and practitioner of macroeconomics who helped guide central banks in two countries, Israel and the US, and mentored a younger generation of economic decision-makers, has died. He was 81.

He died on Saturday, the Bank of Israel said in a statement, expressing condolences.

Fischer, known as Stan, served as vice chairman of the US Federal Reserve from 2014 to 2017 following eight years as governor of the Bank of Israel, adding to a resume that included time at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, spells at the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, and a stint as vice chairman of New York-based Citigroup Inc.

The roster of MIT students he taught and advised included Ben S. Bernanke, who would go on to become Fed chair and called Fischer his mentor; Mario Draghi, a future European Central Bank president and prime minister of Italy; Lawrence Summers, who would serve as US Treasury secretary under Bill Clinton; Greg Mankiw, who would lead President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers; Kazuo Ueda, named Bank of Japan governor in 2023; and IMF chief economists, including Olivier Blanchard, Ken Rogoff and Maurice Obstfeld.

Countless other college undergraduates were introduced to the dismal science by Macroeconomics, the textbook Fischer wrote in 1978 with his MIT colleague, Rudi Dornbusch. The 13th edition of the book was published in 2018.

“It is hard to think of any other macroeconomist alive who has had as much direct and indirect influence, through his own research, his students, and his policy decisions, on macroeconomic policy around the world,” Blanchard wrote of Fischer in 2023. Fischer and Blanchard co-authored Lectures on Macroeconomics, published in 1989.

Dispatched on several occasions to extinguish economic emergencies around the world, Fischer drew academic lessons from his first-hand experience with countries in crisis.

The pattern began in 1983, when George Shultz, then the US secretary of state, invited Fischer to serve on a joint US-Israeli team of experts helping Israel reverse a prolonged period of weak growth, triple-digit inflation and falling foreign exchange reserves. Their work resulted, in 1985, in an economic stabilization program combining a large reduction in government subsidies with the fixing of the exchange rate, a tightening of monetary policy, and wage and price controls — followed, crucially, by the US supplying a $1.5 billion two-year aid package.

That was a prelude to Fischer’s tenure as the No. 2 official at the IMF, the lender of last resort to countries in economic peril. Starting in 1994, Fischer traveled the globe to help resolve interrelated financial crises in Mexico, Russia, Brazil, Thailand, Indonesia and South Korea. His role meant he often overshadowed his boss, IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus. But years later, Fischer credited Camdessus with keeping a sense of calm following the collapse of the Mexican peso in 1994, the first IMF crisis Fischer faced.

Emergency Loans

“I thought Western civilization as we knew it was coming to an end,” but Camdessus “had seen this particular play before,” Fischer recalled. The IMF provided about $250 billion in emergency loans during Fischer’s seven years as first deputy managing director, ending in 2001.

To accept Israel’s 2005 offer to head its central bank, Fischer, an American citizen since 1976, added Israeli citizenship. He conducted business in Hebrew, with an accent that indicated his upbringing in southern Africa.

Under his leadership, Israel’s central bank was the first to cut rates in 2008 at the start of the global economic crisis, and the first to raise rates the following year in response to signs of financial recovery. In 2011, responding to a global downturn, the bank embarked on a series of rate cuts that pushed the benchmark from 3.25% to a record low 0.1% in 2015.

Major changes enacted by Fischer during his eight-year tenure included shifting responsibility for the monthly interest-rate decision from the governor alone to a six-member Monetary Committee, including three outside academics.

“It is testament to Stan’s skillful handling of Israel’s economy that it is one of the very few advanced economies whose output increased every year through the crisis period,” former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King said in 2013.

President Barack Obama appointed Fischer as vice chairman of the Fed Board of Governors under Janet Yellen. Fischer announced his retirement in 2017, a year before his four-year term was to end. He joined BlackRock Inc. as an adviser in 2019.

Africa Upbringing

Fischer was born on Oct. 15, 1943, in Mazabuka, a town in Zambia, the nation then known as Northern Rhodesia. His family was part of a close-knit community of Jews who had emigrated to southern Africa. His Latvian-born father, Philip, ran a general store. His mother, Ann, had been born in Cape Town, the daughter of Lithuanian immigrants, according to a Financial Times profile.

At 13, the family moved to Zimbabwe, then called Southern Rhodesia, where Stanley became active in the Habonim, a Zionist youth group, along with Rhoda Keet, his future wife. In the early 1960s, he spent six months on a kibbutz on Israel’s Mediterranean coastal plain, where he combined learning Hebrew with picking and planting bananas.

He was introduced to economics through a course in his senior year in high school and moved to the UK to study at the London School of Economics, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1965 and a master’s in 1966.

He chose MIT for his doctorate work so that he could study under future Nobel laureate economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow. He said he may have been drawn to macroeconomics “because I was interested in big questions.”

“I had this image of the world as we knew it having nearly collapsed in the 1930s, and that these guys” — the macroeconomists — “had saved it,” he said in a 2005 interview with Blanchard.

He earned his Ph.D. in economics in 1969, worked as an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, then returned to MIT in 1973 as an associate professor. The first course he taught was monetary economics, alongside Samuelson. He became a full professor in 1977.

Bernanke, who earned his Ph.D. from MIT in 1979, traced his interest in monetary policy to a conversation he had with Fischer — “then a rising academic star” — in the late 1970s.

‘Read This’

He said Fischer handed him a copy of A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (1963), by Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz, with the encouragement, “Read this. It may bore you to death. But if it excites you, you might consider monetary economics.”

Bernanke credited Fischer with popularizing the principle that while the Fed pursues goals set by the president and Congress, it has policy independence — freedom to use its tools as it sees fit to achieve those goals.

As chief economist of World Bank from 1988 to 1990, Fischer visited China and India and became, he later said, “gripped by the problem of development.”

After Fischer left the IMF in 2001, he joined Citigroup Inc. as a vice chairman and drew on his experience to lead the bank’s country risk committee.

Fischer declared himself a candidate for the top role at the IMF in 2011, following the resignation of Dominique Strauss-Kahn. At 67, however, he was over the IMF’s age limit of 65 for managing directors, meaning he would have needed a change in rules. The job went to Christine Lagarde.

In 2013, Fischer was thought to be a possible candidate to succeed Bernanke at the helm of the Fed. Obama instead chose Yellen, with Fischer as her deputy.

“In a just world, Stan would have served at some point as Fed chairman or managing director of the IMF,” Summers wrote in 2017. “Fate is fickle and it did not happen. But Stan through his teaching, writing, advising and leading has had as much influence on global money as anyone in the last generation. Hundreds of millions of people have lived better because of his efforts.”